COVID for Choirs – Opening up WA

Living with COVID and keeping your choir viable while you’re at it.

As has been the case throughout this pandemic, your choir must abide by the public health regulations in force at any time. The challenge arising for WA choirs is that we haven’t lived with COVID at all as yet and the fear of doing so, or the reality of doing so, may impact on your choir members in ways that adversely impact the viability of your choir in this phase of opening up to the rest of the country and the world.

Our goal is to assist you and the broader singing community to prepare for this phase, as best you can, while we are still COVID-free and have some time to work through some potentially complex issues in a considered way.

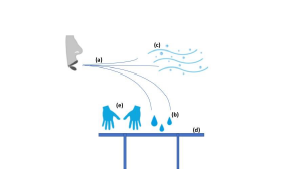

The published public health restrictions planned for WA when we reach the point on 90% full vaccination of the population over the age of 12 are detailed in the “Fact to Share” section below. These will have almost no impact on your ability to rehearse and perform as you are currently doing. The issue that choirs and individual singers have to grapple with is what measures your particular choir feel is appropriate, if any, over and above these restrictions, to address the risk of choir members contracting COVID in the choir setting once COVID is circulating in the WA community.

Every person will perceive the risk that COVID represents to them differently and will have different risk thresholds. Ideally you want to work with your members to arrive at an agreed approach such that your members are comfortable that coming to choir represents an equivalent or lower risk to their wellbeing than undertaking other activities that they are also prepared to continue doing once COVID arrives. You are not striving for or promising zero risk of infection. That’s a promise you can’t keep. You are assisting your members to develop an awareness of the risks they face in every aspect of their lives and to mentally prepare to live with COVID.

The peak bodies for choirs in WA can not and will not mandate specific approaches that every choir should take. This is a matter of individual choice and the collective approach of the specific group of individuals that currently make up your singing group and new members you will attract in the future. However we will provide you with a “shopping list” of measures that your choir should consider and adopt, or not, as your members consider appropriate for their perceived vulnerability and appetite for risk. We will also provide you with another list of scenarios that your members can consider to determine what your group agree to be the most appropriate response should such situations arise for your members in the future. These could form the basis for a series of discussions which will lead to guidelines which you can share with all your current and future members.

Obviously you will be striving to arrive at solutions that suit the needs of the vast majority of your existing members. The willingness of people to be open to the needs of others and accept compromise will assist this and will require some skilful dialogue and, potentially, the sharing of some facts as a basis for these discussions. We have prepared such a fact sheet that we believe represents a reasonable summary of the currently accepted facts as published by reputable health authorities which you may choose to share with your choir members if you see fit.

Having done all this there is still a chance that you will discover that a significant minority of your members have concerns that are unable to be addressed by consensus. In the opinion of the peak community singing bodies in WA, it is most important that choirs continue to survive and prosper through these challenging phases. If your choir discovers that it is going to be challenged through a potential loss of membership, a need to invest in new technology, a need for a new rehearsal venue etc, etc, this is important information for your choir to grapple with sooner than later so that mitigation plans can be put in place and assistance sought.

Your peak singing bodies, Voice Moves WA, SongFest Inc and ANCA (WA) will seek to share information, provide support and make representation as appropriate in support of choirs that identify specific concerns. Please take the opportunity to prepare your choir now and get the conversations started. COVID is coming and we in WA are uniquely fortunate in the world to have some time to prepare. Please use that opportunity.

Click here to download the full article which includes:

Covid Policy Shopping List

Scenarios that Choirs should consider

Covid Facts to share incl references